Communication via fieldbus is highly valued in process automation due to its reliability. Like any installation technology, however, it is not exempt from faults and failures. But what is the actual risk of failure and what availability can be realistically assumed? Calculations often provide an unsatisfactory reflection of the real situation. This results not only in incorrect assumptions, but often in protective measures that are expensive and barely effective.

In practice, to what degree does availability affect whether a fieldbus installation is commissioned? You need to understand what can cause problems and how best to protect against them, so that you can take preventive measures and ensure increased fieldbus availability. However, availability calculations are based on descriptions, assumptions, and observations from the theory of probabilities. Here at Pepperl+Fuchs, we have discovered from many years of interaction with users that these calculations are based on assumptions that are sometimes unrealistic, and sometimes just plain wrong. Of course, the results of such calculations do not really reflect reality.

What do we mean by actual availability?

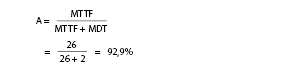

The International Electrical Vocabulary (IEV) has 47 different definitions of the term availability and, accordingly, different ways of calculating it. Stationary availability is usually called availability (A) for short. It is defined as the mean value of current availability in a time interval. The mean time to failure, called MTTF, and the mean down time, called MDT, can be used for a simplified calculation of the stationary availability, provided these values are constant. In this case, the following formula is used for the calculation:

Often, the inverse of the Lambda failure rate for a product or series of products is mistakenly used to calculate the MTTF, such as for a fieldbus segment. But this procedure reflects only the random failure of the component(s). This means that important systematic criteria are not being taken into account. In practice, these criteria play a crucial role in availability: When environmental influences as well as the mode of operation and its effect are not accounted for in the calculation, a significant discrepancy arises between the mathematical theory and the effect in practice when it comes to process automation. However, a brief glance at alarm and failure statistics makes it very clear that it is precisely the effects of the mode of operation and environmental conditions that are responsible for faults much more frequently than random events that cause component failure.

An example shows the difference

The extent to which this type of one-dimensional view can distort reality when calculating availability is shown by a simple example: If a person in his role as employee is used instead of the process system, the result is an MTTF of 1401 years or 72 800 weeks according to the above-mentioned procedure. But this value takes into account only the ‘total failure’ i.e., possible death of an employee, which certainly does not accurately reflect the employee’s actual availability in his professional life. If you further assume that a replacement is found for a failed employee after six weeks (=MDT), the availability is calculated as:

Of course, important aspects of everyday working life remain unaccounted for. Much more frequent causes of absence from the workplace are vacation, illness, doctor’s appointments, or business trips, which can occur several times a year. If you assume that a failure of on average two weeks occurs twice a year for these reasons, the availability is calculated as:

Reduction of failure risks

Finding the right method of calculating availability is just the first basic step. Once you have calculated reliable figures for the actual availability of a plant, it follows that you must take measures to reduce the failure rates effectively and thus increase availability. Systematically, there are four methods to protect against a component or part of a system failing and thus positively influence the MTTF.

First: Preventive measures and procedural instructions must be given. The correct and protective handling of technology is often enough to help reduce failures significantly.

Second: The predictive, automated handling of faults. With this method, techniques and components are used that have been specially developed to detect and isolate typical faults in a targeted and proactive manner, before they can spread. The impact of the fault remains limited to a deactivated device, while the plant itself remains in operation. For example, if a measuring device connection is deactivated in the case of a short circuit, but the fieldbus segment remains unaffected, because the failure of an individual measuring part is tolerable.

Third: The detection of faults through diagnostics. With this method, discrepancies between the actual status and the best possible status are detected through monitoring and reported to the control room. Before this can have a negative impact on the overall function, proactive intervention can be taken. For example, if you measure a change in the frequency of filling level sensors using a tuning fork, this indicates that the sensor has become jammed. The problem can then be corrected.

Fourth: Redundancy. This protects against failures whose causes have to be investigated in the device itself. Redundancy is indispensable if these faults cannot be avoided in any other way, but must absolutely be controlled to ensure safety or plant availability. This is the case for power supplies and control technology boards or for field devices where the measuring circuit is required to have a very high level of availability.

For more information contact Mark Bracco, Pepperl+Fuchs, +27 (0)87 985 0797, [email protected], www.pepperl-fuchs.co.za

| Tel: | +27 10 430 0250 |

| Email: | [email protected] |

| www: | www.pepperl-fuchs.com/en-za |

| Articles: | More information and articles about Pepperl+Fuchs |

© Technews Publishing (Pty) Ltd | All Rights Reserved