An upgraded control system can significantly improve efficiency and productivity; enhance safety; increase reliability; provide better data management; support new technologies; reduce risks associated with unsupported hardware and software; comply with regulations; and increase the overall performance of a manufacturing process. However, the industry is plagued with control system upgrade myths and misconceptions that can lead to liability issues, project delays, cost overruns and decreased plant performance. To help organisations understand and avoid these myths, we explore the most common misconceptions and provide recommendations for mitigation.

Myth 1: We are only duplicating what we have now. In reality, companies will take the opportunity provided by a project to optimise the design to ensure cost saving. A number of small PLCs (the old way) will become Remote Input Output (RIO) and control will be consolidated into a larger PLC (the new way). Communication hardware and protocols will change to newer technology and may not support old communication methods. This all results in a control system that does not have any resemblance to the old system.

Myth 2: We are doing a like-for-like replacement. In reality, sometimes there are no like-for-like new technologies available, and a different solution will be required. New and additional technologies may slip in as part of the project. The notion is that while you’re upgrading, you might as well include a few new additions and functions. The end result is not a like-for-like replacement, but a different new system.

Myth 3: It will be easy as we are not changing anything. In reality, everything changes. All systems will need to be retested, from field to scada to databases (complete loop testing), to ensure safe and optimum operation.

Myth 4: It is only a control system automation project. In reality, it never stays as automation only. Mechanical and/or electrical equipment will be added or replaced at the same time. Whole new processes may even be added and included in the project. The notion is that since the plant is down anyway, one may as well use the downtime. This means that the new system needs to include the new process or equipment, and the new untested equipment needs to be commissioned as part of the project.

Myth 5: All control systems, equipment and processes are currently working fine. In reality, years of a ‘short-term fix turned into permanent fix’ will need to be returned to standard. Old and faulty equipment that was bypassed to make the plant run will need to be repaired and recommissioned. Interlocks that were bypassed to make the plant run will need to be returned to the correct state.

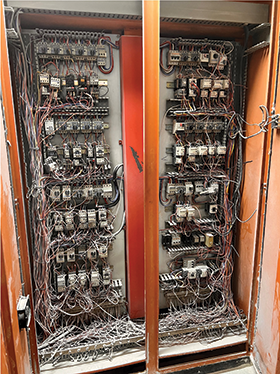

Myth 6: Field devices are all in working order. In reality, most plants have faulty instrumentation that was bypassed or de-activated to make the plant run before the start of the upgrade project. These will need to be repaired or replaced to operate the plant according to the design. Due to the plant not being operated for a period of time, panel components (contactors, auxiliaries, etc.) are often ‘pirated’ and need to be replaced. Maintenance personnel will replace (pirate) a faulty component from the offline panel rather than trudge all the way to the store to fetch a new one. This may become apparent only during the commissioning phase, but because these components are an integral part of the control system, it will present a challenge to the commissioning team. The notion is “you touch it, you own it!”.

Myth 7: Panel layouts and wiring are standardised. In reality, no panel drawings exist any more, or panel drawings exist but do not resemble anything inside the actual panel. Due to years of additions and changes, wiring is most often not standard, or each panel has its own standard.

Myth 8: We used software development standards throughout. In reality, years of ‘short-term fix turned into a permanent fix program changes will need to be returned to standard. In other cases, control system standards are old and need to be redefined to conform to current best practice. Standards change as control systems and communication technology improve. New best practices are defined based on the changed environment resulting in changes of the standards, which should usually be accompanied by employee training.

Myth 9: Our control philosophy is up to date. In reality, due to the age of the plant, no defined control philosophy exists, or the control philosophy is outdated and does not have all equipment or instrumentation included. In many cases, plant operators, managers and engineers have different opinions as to how the plant needs to operate, resulting in a lot of rework and misunderstanding.

Myth 10: There is no inter–PLC communication. In reality, inter-PLC communication will pop up during commissioning, as another PLC was used in the plant to do ‘”something small because we ran out of I/O” on the PLCs to be upgraded. In extreme cases, inter-PLC communication may even go via the scada system. A situation like this that crops up during commissioning often results in delays and rework.

Myth 11: The scada system will not change. In reality, due to combining PLCs of differing ages and implementers, old naming will have to be standardised, so PLC tag-names will change. This will result in an update to the I/O server directly affecting the addressing of the tags in the scada. In some cases, control logic belonging in the PLC will be found running in the scada, requiring rework in the scada or PLC. Sometimes variables will be scaled in the scada. This will then have to be removed and done in the PLC, resulting in more commissioning delays.

These common myths and misconceptions can result in unintended additional costs and project time-line over-runs and loss of production. Therefore, proper planning and preparation is crucial in ensuring the success of a project.

The following mitigation steps are proposed:

• Define the project battery limits: Identify who is responsible for what. Define the responsibilities of the contractor, engineering, maintenance, electrical, instrumentation production, operation and automation departments. Without, for instance, a process engineer or experienced operator who knows where instruments are located, loop-checking will be time-consuming if not impossible.

• Confirm and approve the control philosophy: Before starting the project, ensure you have an authorised and approved control philosophy. This will ensure that in the event of doubt regarding plant operational processes, sequences or interlocks, the control philosophy will be the deciding factor.

• Define and approve PLC and scada standards and functional design specification: Like most for projects, proper documentation will remove uncertainty, misunderstanding and grey areas.

• Audit and define inter-PLC communication: Look for missing parts in the PLC and scada systems that may be the result of inter-PLC communication. Do not assume that inter-PLC communication will continue to operate flawlessly after the upgrade. Rather incorporate all control into the new PLC if at all possible. This will require additional effort, but it is essential to ensure that everything works as intended and save time in the long run.

• Audit the field instrumentation: Check the state of the field panels and instruments before commissioning commences. Do not assume all instruments are operational. If you don’t know about a proxy that has been bypassed or bridged in the field, it will become your problem and delay commissioning.

• Audit panels, switchgear, contactors and auxiliaries: Audit these components before the start of commissioning. Components may be missing or may have changed since your last visit. Take photographs that can be used as comparison to identify possible changes.

• Audit the equipment state: Define the state of the equipment before starting the project. Do not assume that all production equipment is operational. It may be expected of you to make a piece of equipment operational that has not worked for years (due to mechanical or electrical issues). Without proof that it did not work before the start of the project, you will be expected to get it operational.

• Audit PLC connections: Check for inter-PLC communication links. You want to avoid arriving for commissioning to find unexpected communication between PLCs. Also ensure that PLCs communicate directly and not via the software I/O server.

• Review all scada scripts: Check the scripts for possible control logic and variable scaling that is best done in the PLC. Document this and move it to the PLC. This will ensure no conflicting instructions are sent to switchgear from both the PLC and the scada.

• Spend time in the running plant to experience actual operations. Take notes, videos and photographs: Take videos and notes to ensure that you witness the running plant. In doing this, you will be able to see start and shut sequences, alarm handling and what equipment is operational. This initial investment will save days of unnecessary headaches and time during the commissioning period.

In conclusion, proper planning is crucial to the success of a project. By following these mitigation steps, you can ensure that you have the right control philosophy, standards and communication to avoid issues during commissioning. Of course, these myths, misconceptions, and mitigating actions will only be present in some plants for a control system upgrade; but consider this an excellent checklist to follow to avoid costly delays and nasty surprises during project execution.

| Tel: | +27 12 349 2919 |

| Email: | [email protected] |

| www: | www.iritron.co.za |

| Articles: | More information and articles about Iritron |

© Technews Publishing (Pty) Ltd | All Rights Reserved